The rapid evolution of dentistry during the past few decades has resulted in advances in materials and procedures allowing dentists to provide results for their patients that can closely replicate nature. The standards of care have been improved in every dental discipline. Orthodontists routinely move teeth in adults with debilitated dentitions to enhance periodontal health and place teeth in predetermined positions to accept ultraconservative restoration. Dental implants are no longer simply inserted randomly but are preplanned to be in position to create the same emergence profile, contour, and function as natural teeth. Periodontal procedures have advanced to the point of avoiding aggressive pocket reduction resulting in long teeth and the loss of the interdental papilla. The dental team that closely works together can usually provide a huge advantage for the patient.

Until the late 1970s, the public looked at dentists with fear and associated dentists with pain. In their minds, dentists just “drilled, filled, and billed.” A group of dentists, at that time, began to perform elective dental services on their patients for purely aesthetic reasons. These inventive aesthetic pioneers changed the public’s perception of dentistry, and people began to appreciate and desire elective aesthetic procedures. However, a large number of dentists looked upon these services as being unnecessary and even detrimental to the patient’s oral health. The demanded that these “aesthetic quacks” be stopped and their right to practice revoked.

How times have changed! All the dental specialties have now gotten into the act. Orthodontists today do not just treat “crooked” teeth but align tissue levels, repair periodontal defects, and align teeth to exacting positions to accommodate a proposed restoration. Periodontists do not merely treat disease but electively aim to place tissue levels with proper aesthetics.

The aesthetic dental pioneers and rapid changes in techniques and dental materials opened a dental revolution and inspired a revolution in dental education. We are no longer living in G. V. Black’s and Edward Angle’s world of conventional rules and standards. Dentists are now thinking outside the box, allowing the patient’s face to dictate the treatment, and patients are benefitting enormously.

The restorative dentist should be the team leader, like a quarterback executing the plays to achieve the desired treatment outcome. The clinician is expected to deliver an excellent final outcome, and that is a big obligation! To begin with, the restorative dentist must have a clear vision of the desired outcome in order to plan and sequence the necessary steps to achieve it. In addition, one must also be familiar with the procedures available in the various dental disciplines and guide the patient accordingly.

First and foremost, the clinician, as quarterback, should listen to the patient and establish realistic treatment objectives based on the patient’s needs and expectations, while taking into account any budgetary considerations. The restorative dentist should create the vision of the desired result and establish a blueprint (treatment plan) on how to execute the plan. A treatment sequence is determined that often involves periodontics, orthodontics, and implantology. Misshapen and malformed teeth are usually first built to ideal proportion and are positioned to facilitate restorative treatment. The quarterback (clinician) must interact with the various players (specialists) throughout treatment, checking and taking radiographs during finishing to visualize root proximity, angulations, and if there is adequate space available for implants. Sometimes, the restorative dentist may even choose to temporize teeth before specialty treatment is completed to help visualize proposed tooth positions and to verify if any treatment changes might be needed. Once everything is in place, the final restorative work is fabricated and delivered.

THE ROLE OF THE ORTHODONTIST

Historically, orthodontists were treating teenagers and not accustomed to dealing with patients requiring restorative intervention. Adolescents generally require little or no restoration. However, in the 21st century, orthodontists are often treating adults who have not benefited from preventive dentistry, and have serious restorative and/or periodontal needs. The objectives of orthodontic treatment may be totally different for the restorative patient as compared to a nonrestorative patient. For example, (1) the teeth may have to be moved by the orthodontist to place them in an ideal position to be restored and, sometimes, it may be beneficial to temporize these teeth before or during orthodontics to achieve a better vision and perspective of the final result; (2) orthodontics may be required to correct tooth malposition that is compromising to the patient’s oral hygiene; and (3) orthodontics may be performed for elective or nonelective periodontal reasons.

The restorative patient may require tooth positioning that may be totally different from the nonrestored adolescent patient with all of his or her natural teeth. The teeth may be worn, resulting in discrepancies in the incisal and occlusal planes. There may be fractured, misshapen, or malformed teeth, such as peg laterals or narrow anteriors lacking anatomical form. Missing teeth may have led to midline asymmetry and edentulous areas lacking the require space to accommodate the desired tooth replacement. The patient may have periodontal bone loss, missing papilla, and uneven gingival margins. Therefore, current orthodontic objectives include (1) establishing a stable and functional occlusion, (2) enhancing the health of the periodontium, and (3) improving dental facial aesthetics.

THE ROLE OF THE PERIODONTIST

There are times when orthodontics provides the best benefit for the periodontal patient:1,2 (1) by aligning crowded or malposed teeth, periodontal maintenance is easier; (2) vertical orthodontics can be utilized to improve osseous defects; (3) orthodontics can improve the position of the gingival margins; (4) high-intensity orthodontic extrusion can create forced eruption of fractured teeth; (5) orthodontics can be used to regenerate lost papilla; and (6) orthodontic care is often necessary to optimize the position of implant placement.

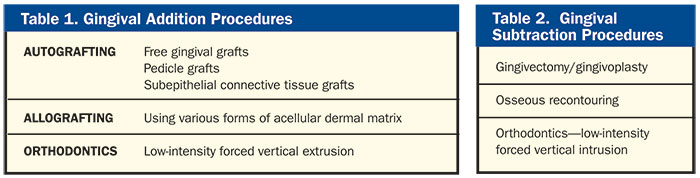

Various periodontal procedures exist, and are being developed, to alter gingival position for health and aesthetics3-7 (Tables 1 and 2).

|

Facially Generated Treatment Planning

In a world where dental standards are being rewritten, and the dentist has been recognized as an oral plastic surgeon, the dental paradigm has shifted to what is known as facially generated treatment planning. In other words, “the face dictates the treatment.” Every dental treatment plan begins by evaluating the facial aesthetics first by referencing the patient’s lips, cheeks, skin, etc. We always begin by evaluating the maxillary tooth position and gingival levels relative to the face to evaluate if and how things must be changed. We cannot establish the occlusal scheme until we determine the final desired position of the anterior teeth; this information will then dictate the vertical and edge-to-edge position as well as the pathways of guidance.

When establishing a treatment plan, the restorative quarterback should always begin by establishing a final aesthetic vision. If we don’t know what we are trying to achieve, how can we expect to predictably get there? Once we have determined the aesthetic goal, the health of the teeth and periodontium must be evaluated to create a dental result that is easily maintainable, with a stable and functional occlusion that is in in facial harmony and muscle balance.

The orthodontist is often the first in line in a decision process that can affect the patient’s appearance for the rest of that individual’s life.8 Traditionally, orthodontists evaluated a patient’s facial appearance both resting and during movement in 3 dimensions: vertical, horizontal, and sagittal. It is most important to consider a “fourth dimension” too: time! Time is the “dental twilight zone,”9 as it is difficult to predict how the patient’s facial appearance will change with age. We must do everything we can dentally to help protect our patients’ faces from the ravages of time.

As previously stated, the first thing we evaluate in the treatment planning protocol is the maxillary anterior tooth position.10-12 It is important to observe how much of the anterior teeth are showing at rest and when the patient smiles. As people age, their maxillary anterior tooth display decreases, and their mandibular tooth display increases.13 We must evaluate if their lips are full, thin, or hypermobile. Then, one can compensate for many of these factors in any treatment plan.

Once the desired position for the maxillary anterior teeth has been established, the position and form of the lower arch is evaluated.11 Lower arch discrepancies affect the position of the upper arch as they must fit together. Lower arch discrepancies result in deviations in the incisal and occlusal planes. Just as architects design structures from the ground up, dentists must do the same. We must ask ourselves if the lower arch is in proper alignment to accommodate the proposed changes to the upper arch. If not, we must begin by redesigning and placing the lower arch in ideal position using restorative techniques, orthodontics, and/or surgery.

We begin by evaluating the position and form of the mandibular incisors for midline, arrangement, overbite, overjet, wear, mobility, fractures, signs of disharmony, and pathways of guidance. We then observe the posterior teeth looking for position, plunger cusps, wear, microfractures, abfraction, supereruption, etc. We ask ourselves if we can simply reshape or restore the teeth, or whether we need to move them orthodontically.

Once we have determined the desired aesthetic result and the corresponding position of the teeth, we must establish the arrangement, contour, and shade the patient desires. Personality and age must be taken in account and, in addition, the length, shape, width, and surface texture. There are many different restorative options available: composite resins, ceramic veneers, all-ceramic crowns, metal ceramics, implants, and removable prostheses. We must consider the biological, spatial, and logistical issues when choosing what type of restoration and which material to use:

- How much resistance and retention is there on the prep? We need adequate prep length and retentive ferrule.

- Is the tooth biologically strong, or has it been weakened by endodontics or extensive restoration?

- Are there light or heavy mechanical forces on the dentition? We must evaluate bruxism, clenching, attrition, abrasion, etc.

- Do we have adequate space for our ideal restorative material, or do we need to change our material choice or create more available space?

- What are the chemical influences on the proposed restoration (acidity, erosion, perimolysis)?

- What material does our lab prefer? As with everything else, certain people prefer one product to another.

CASE REPORT

Diagnosis and Treatment Planning

Our patient first presented to obtain a second price quote for upper implants to replace teeth Nos. 10 to 12 (Figure 1). He explained that his problems began when he fractured tooth No. 10 off at the gumline. It was replaced with a cantilever pontic that utilized the canine (No. 11) as an abutment. He was told that the canine was a very strong tooth and would be able to support the missing lateral indefinitely. However, the canine soon fractured off also, followed by the first bicuspid. An acrylic partial denture was then fabricated to replace the 3 missing teeth. The dentist also recommended implants to permanently replace the missing teeth, but the patient found the proposed cost to be excessive and he wanted a second opinion and price quote.

|

|

| Figure 1. Preoperative photo. Patient missing teeth Nos. 10 to 12. | Figure 2. Several years later, more teeth have been lost. |

|

|

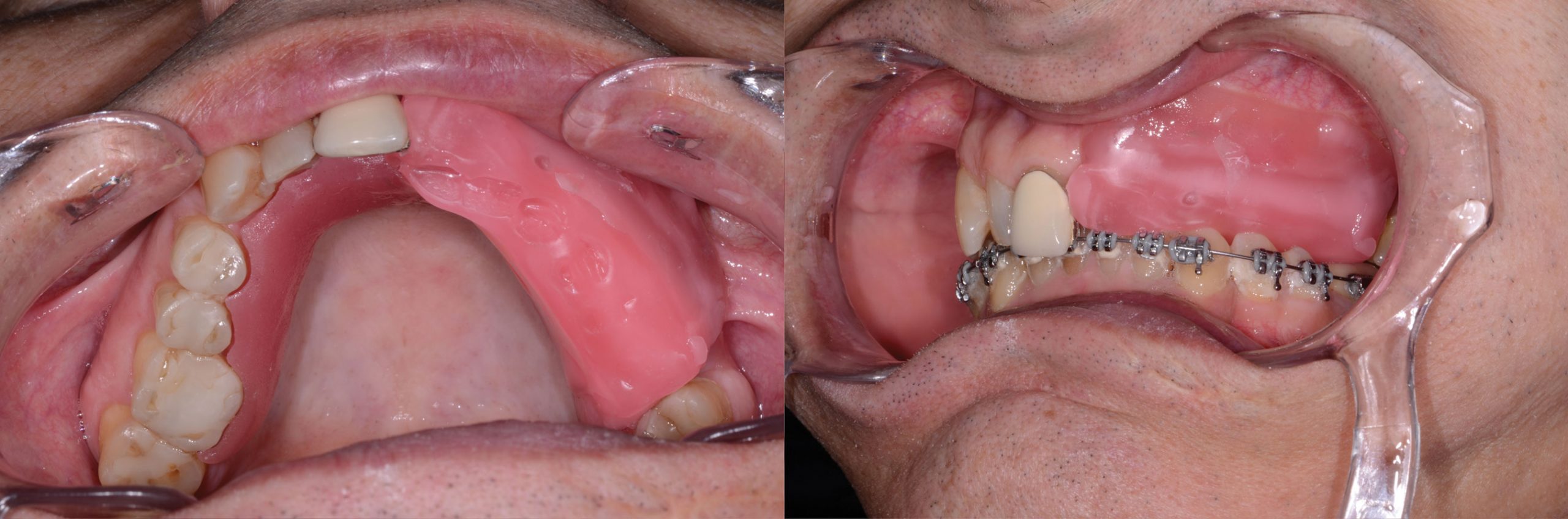

| Figure 3. Lower arch collapse did not allow adequate space for a restoration. | Figure 4. The surgical implant stent. |

Evaluation of the position and shape of the upper anterior teeth found them to be acceptable. The midline was not totally centered, and the teeth were slightly canted, but this did not bother the patient.14,15 However, the lower teeth were not aligned, resulting in posterior bite collapse and an excessively deep bite, creating excessive forces to the upper anterior teeth. It was thoroughly explained to the patient that his problem included his lower teeth, and that lower orthodontic treatment was needed before placing the upper implants and fixed prosthesis. He looked at me as if I was crazy and exclaimed that dentists just try to “rip off patients for as much money as possible.” All he wanted was “3 #&$%! upper teeth.” What did the “lower teeth have to do with replacing 3 upper teeth?” None of his previous dentists ever said he had problems with his lower teeth. He left without saying thank you or goodbye.

Interestingly, a few years later, he reappeared for another consultation. He had subsequently snapped off his crown on tooth No. 9 and had yet another partial denture made (Figure 2). Tooth No. 13 was now extremely mobile and painful. His dentist told him that his teeth were weak and that it was best for him to remain in a partial, as other teeth would probably break as well. The patient did not want to continue losing his teeth, and was now open to really listen to what I had tried to explain to him several years earlier.

The lower arch had now collapsed to a point where there was not adequate space to create an upper fixed restoration (Figure 3). The lower left canine was rotating and sliding buccally over the bicuspid distal to it. I explained that this canine was the probable culprit that caused the loss of the lateral, canine, and first bicuspid. This time, the patient had an open mind and seemed to understand and accept his predicament. We decided to simultaneously begin lower orthodontic treatment to align the lower arch to ideal and to place implants in order to have a fixed porcelain restoration replacing the missing upper teeth. Total treatment time of 8 to 10 months was anticipated.

Clinical Protocol

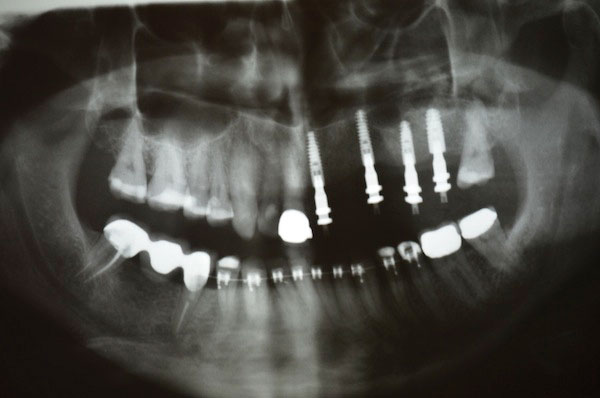

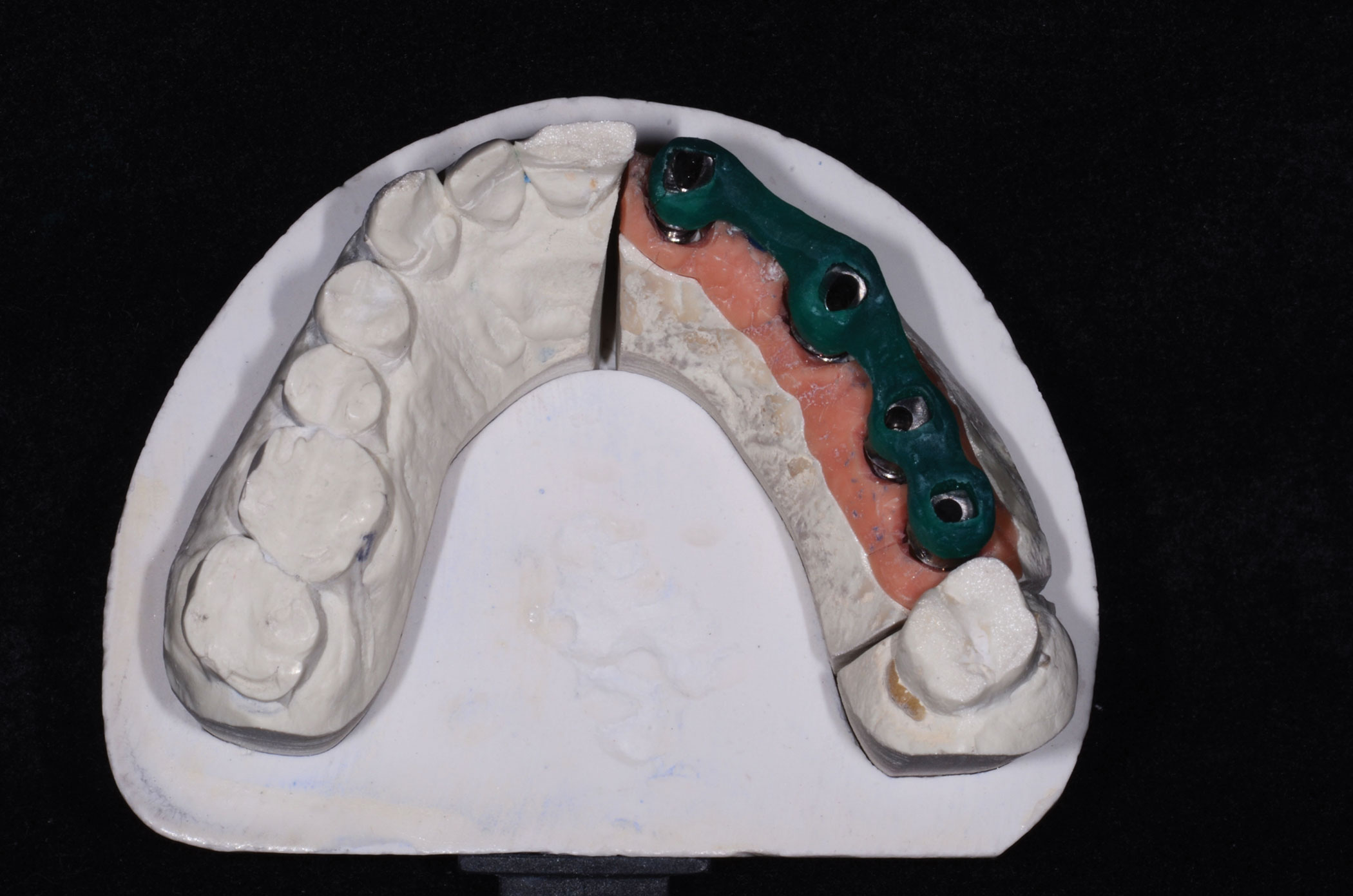

A diagnostic setup and surgical implant stent were created in order to place the implants in their specified position (Figure 4). The stent not only showed us the position of the teeth, but also allowed us to align the correct vertical angulation and depth, permitting us to visualize the position of the proposed tooth in full form and contour. Implants (ANKYLOS [DENTSPLY Implants]) were placed in position Nos. 9, 11, and 12; tooth No. 13 was extracted and was replaced with an immediate implant (Figure 5). ANKYLOS implants were chosen because they are placed subcrestally, and the conical, 6° Morse taper abutment places no load on the abutment screw. By having no micromovement, there is little to antagonize the hard and soft tissues resulting in papilla preservation, with no subsequent bone loss and a natural looking emergence profile.

|

| Figure 5. ANKYLOS (DENTSPLY Implants) implant placement using the surgical stent. |

|

| Figure 6. ANKYLOS transfer copings. |

|

| Figure 7. Verification using a panoramic radiograph of the ANKYLOS transfer copings. |

|

| Figure 8. Bite registration using an acrylic baseplate and wax rim. |

|

|

| Figure 9. Lab made provisional bridge (Telio Lab [Ivoclar Vivadent]), using ANKYLOS temporary abutments. | Figure 10. The provisional bridge in place. |

|

| Figure 11. Teeth Nos. 7 and 8 were prepared, and dentin and porcelain shades taken. |

|

|

| Figure 12. Teeth Nos. 7 and 8 receive the provisional (Luxatemp Ultra [DMG America]). | Figure 13. Parallel metal ANKYLOS abutments. |

Six months passed, the upper implants were integrated, and the orthodontics had advanced to the point where the lower arch was nearly aligned. It was decided that it was time to fabricate a fixed upper temporary prosthesis. ANKYLOS transfer copings were placed and a Panorex radiograph was taken to verify position and alignment (Figures 6 and 7). The author prefers to take open-tray implant impressions and still use the “old school” method of joining the implant transfers with dental floss and pattern resin. This technique prevents movement of the transfers and virtually guarantees an accurate impression and perfectly fitting implant abutments. A vinyl polysiloxane putty (Honigum MixStar Putty [DMG America]) and light-body wash (Kopy [Dental Savings Club]) were used for the final impression. The Kopy light body is extremely flowable, and the Honigum Putty is an extremely firm material ideally suited to implant impressions as it firmly locks the transfers in place, preventing any micromovement that could result in inaccuracies when pouring the stone model. A wax rim on an acrylic baseplate was used to register the bite (Figure 8).

An acrylic (Telio Lab [Ivoclar Vivadent]) provisional bridge was fabricated by the laboratory team using ANKYLOS temporary abutments (Figure 9) and placed in the patient’s mouth (Figure 10). This allowed the patient to experience fixed teeth for the first time in years. In addition, aesthetics were evaluated and, most importantly, the accuracy of the master impression was verified, assuring us that the permanent restoration would fit accurately. The lower orthodontic brackets were removed and a lingual retention wire placed on the lower anterior teeth.

Upon seeing and feeling the fixed provisional restoration in his mouth, our patient began to feel excited and started to appreciate his treatment plan. Although he had previously and emphatically made it clear that he had no interest in restoring more than the missing teeth, he was now interested in enhancing the look of his other front teeth. Teeth Nos. 7 and 8 were prepared, dentin and porcelain shades with shade photos taken (Figure 11), and then the teeth were provisionalized (Luxatemp Ultra [DMG America]) (Figure 12). Our treatment plan called for a 5-tooth porcelain-to-zirconia fixed restoration, attached to metal implant abutments by lingually placed Dentatus set screws. The lingual set screws allow the bridge to be retrieved should a future repair be needed. They also are not influenced by implant position, nor do they weaken the porcelain, as often occurs with larger screws placed through the occlusal surfaces. By eliminating the use of cement, the risk of peri-implantitis is also reduced.16,17

Our lab team fabricated parallel individual metal implant abutments (Figure 13) with occlusal screw access to the ANKYLOS implants and lingual screw taps for the tiny Dentatus screws to secure the zirconia prosthesis (Figure 14). An acrylic jig was supplied to be able to easily place the abutments in the patient’s mouth (Figure 15).

When the metal abutments and zirconia frame (Prettau [Zirkonzahn]) were placed in the patient’s mouth, the fit was precise (Figure 16). Utilizing an open-tray impression technique with the fabrication of a temporary bridge using temporary abutments ensures the predictability of fit of the final restoration. An acrylic bite registration material (LuxaBite [DMG America]) was placed over the zirconia frame, and then a new bite registration was taken. This material eliminates any movement and inaccuracies that would otherwise be associated with the use of vinyl polysiloxane bite registration materials. The zirconia frame and abutments were then removed and replaced with the acrylic provisional bridge.

Lithium disilicate (IPS e.max [Ivoclar Vivadent)] was layered over the zirconia frame (Figure 17). An appointment was made to place the bridge and take the final impression for teeth Nos. 7 and 8 that had previously been prepared and temporized. To our complete surprise, the patient asked if we could restore his upper right arch as well. Had he ever come around! This was most definitely not the same man who we had first met!

|

|

| Figure 14. The lingually placed Dentatus set screws attach the zirconia frame. | Figure 15. An acrylic jig enables easy placement of the abutments in the patient’s mouth. |

|

|

| Figure 16. The zirconia frame (Prettau [Zirkonzahn]) with Dentatus set screws in place. | Figure 17. The zirconia frame was layered with lithium disilicate (IPS e.max [Ivoclar Vivadent]). |

|

|

| Figure 18. The restored dentition. | Figure 19. Lingually placed Dentatus screws secure the bridge and a thin coating of TempBond Clear (Kerr) was used to seal the margins. |

|

| Figure 20. A very happy patient. |

The upper right quadrant was prepared, impressed, and a Luxabite registration taken. Lithium disilicate (e.max) restorations were fabricated and cemented with a glass ionomer cement (Fuji II [GC America]) (Figure 18). A small amount of TempBond Clear (Kerr) was placed at the margins of the zirconia bridge, which was then secured with the lingually engaging Dentatus screws (Figure 19). The restoration was then checked in protrusive, and right and left excursive movements, and adjusted as required to correct any occlusal discrepancies. After many years of dealing with less than satisfactory results and ongoing problems, our patient was finally one happy camper (Figure 20)!

CLOSING COMMENTS

The importance of a complete treatment plan, with a clear vision of the final outcome, cannot be over emphasized. The clinician must always realize that patients did not go to dental school and can often be misinformed by being told what a previous dentist assumed that they wanted to hear. In our office, every one of our treatment plans follows the same protocol of first establishing the position of the upper anterior teeth and then determining if the lower teeth are in the correct position to support and maintain them in health.

If we take the time to thoroughly educate our patients by telling them what we know, it is the author’s belief that many more patients would opt for ideal treatment. It is this author’s opinion that people do not want to intentionally hurt themselves. Oftentimes, they just are not adequately prepared to make an educated and fully informed decision. Just as there are no shortcuts in medical surgical procedures, the same standards should apply in dentistry.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank the following people: Eric Chatelain, DMD, for implantology; George Pappas, DMD, MSc, for orthodontics; and Bassam Haddad, MDT, for oral design (Vivaclair dental lab, Quebec, Canada).

References

- Kokich VG, Spear FM. Guidelines for managing the orthodontic-restorative patient. Semin Orthod. 1997;3:3-20.

- Kokich VG. Esthetics: the orthodontic-periodontic restorative connection. Semin Orthod. 1996;2:21-30.

- Kois JC. Altering gingival levels: the restorative connection. Part I: biologic variables. J Esthet Restor Dent. 1994;6:3-9.

- Miller PD Jr. Reconstructive periodontal plastic surgery. J Tenn Dent Assoc. 1991;71:14-18.

- Heithersay GS. Combined endodontic-orthodontic treatment of transverse root fractures in the region of the alveolar crest. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1973;36:404-415.

- Ingber JS. Forced eruption. I. A method of treating isolated one and two wall infrabony osseous defects—rationale and case report. J Periodontol. 1974;45:199-206.

- Brindis MA, Block MS. Orthodontic tooth extrusion to enhance soft tissue implant esthetics. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67(suppl 11):49-59.

- Sarver DM, Ackerman MB. Dynamic smile visualization and quantification: Part 2. Smile analysis and treatment strategies. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;124:116-127.

- Mechanic E. Anterior tooth challenges, part 4: Canines in the lateral position. Dent Today. 2014;33:84-89.

- Sarver DM. The importance of incisor positioning in the esthetic smile: the smile arc. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001;120:98-111.

- Kokich V. Esthetics and anterior tooth position: an orthodontic perspective. Part II: vertical position. J Esthet Dent. 1993;5:174-178.

- Lee EA. Aesthetic crown lengthening: classification, biologic rationale, and treatment planning considerations. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent. 2004;16:769-778.

- Kokich VG. Esthetics and vertical tooth position: orthodontic possibilities. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1997;18:1225-1231.

- Vig RG, Brundo GC. The kinetics of anterior tooth display. J Prosthet Dent. 1978;39:502-504.

- Kokich VO Jr, Kiyak HA, Shapiro PA. Comparing the perception of dentists and lay people to altered dental esthetics. J Esthet Dent. 1999;11:311-324.

- Wadhwani CP. Peri-implant disease and cemented implant restorations: a multifactorial etiology. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2013;34(special issue 7):32-37.

- Wilson TG Jr. The positive relationship between excess cement and peri-implant disease: a prospective clinical endoscopic study. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1388-1392.

Dr. Mechanic received his bachelor of science (1975) and doctor of dental surgery (1979) degrees from McGill University. He maintains membership in numerous professional organizations, including the American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry, the Academy for Dental Facial Esthetics, the American Society for Dental Aesthetics, and the European Society of Cosmetic Dentistry. He practices aesthetic dentistry in Montreal, Canada, and he is the aesthetic editor of Canada’s Oral Health dental journal, and is on the editorial board of Dentistry Today. He also is the co-founder of the Canadian Academy for Esthetic Dentistry, program coordinator of the University of Toronto Advanced Restorative Continuum, and is recognized as a leader in continuing dental education. His work has been profiled in magazines, television, and radio. He can be reached at info@drmechanic.com.

Disclosure: Dr. Mechanic reports no disclosures.